„We now live with illness and disabilities from which we used to die”.

Sir Cyrile Chantler (2002)

In the last couple of years I always asked myself why is that?!

Today we live in very odd times where technological improvement has led to an endless supply of information and that should lead to an improvement in the quality of life. If we look at the past century, perhaps the greatest human accomplishment was the remarkable increase in life expectancy. As an example, in the United States life expectancy at birth, in over 110 years since 1900 to 2010, went from 47,3 to 78,7 years. First, this increasing length of life resulted from declines in infectious diseases and deaths concentrated among the young. Life expectancy continued to increase in the last decades of the 20th century due in large part to declining mortality from heart disease (Crimmins, 2015).

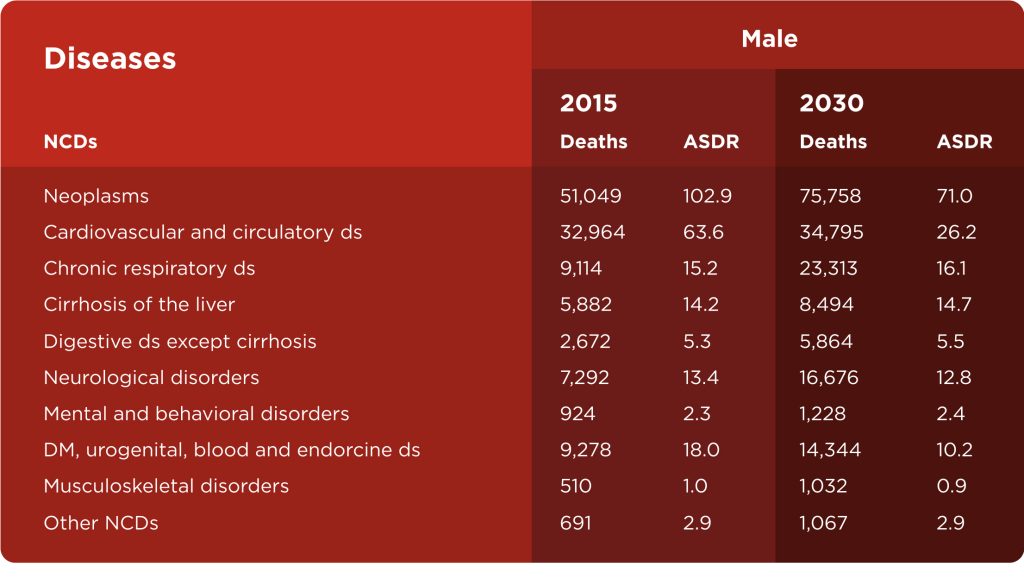

Living longer doesn’t mean that we live better. If we take a closer look into the study by Park et al. (2018) that that research projections of years lived with a disability and deaths caused by various chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs), we can see those projections for 2030 as an increase in both categories. Table 1. summarizes the projected number of deaths and age-standardized death rates for 21 cause clusters in 2030 in comparison with those in 2015.

Chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death globally (60% of all deaths) and they are responsible for killing more people each year than other causes combined. The main types of NCDs are cardiovascular diseases (such as heart attacks and stroke), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases (such as asthma), and diabetes. Physical inactivity has been identified as the 4th leading risk factor for global mortality (6% of deaths globally) and even overcoming obesity and overweight as a risk factor (Barbosa Filho et al., 2014). Musculoskeletal injuries and pain (especially lower back pain) are important in this context of NCDs and physical inactivity because they are a leading cause of years lived with disability (Wu et al., 2020).

If I was writing this about the coronavirus, this would be a more talked about topic that would probably receive a bigger audience and greater recognition, but I am not writing about the coronavirus. I am writing about the pandemic of physical inactivity about which healthcare professionals have been talking for a very long time, but it seems it is not showing much success as many are overlooking this problem.

What do we do now?

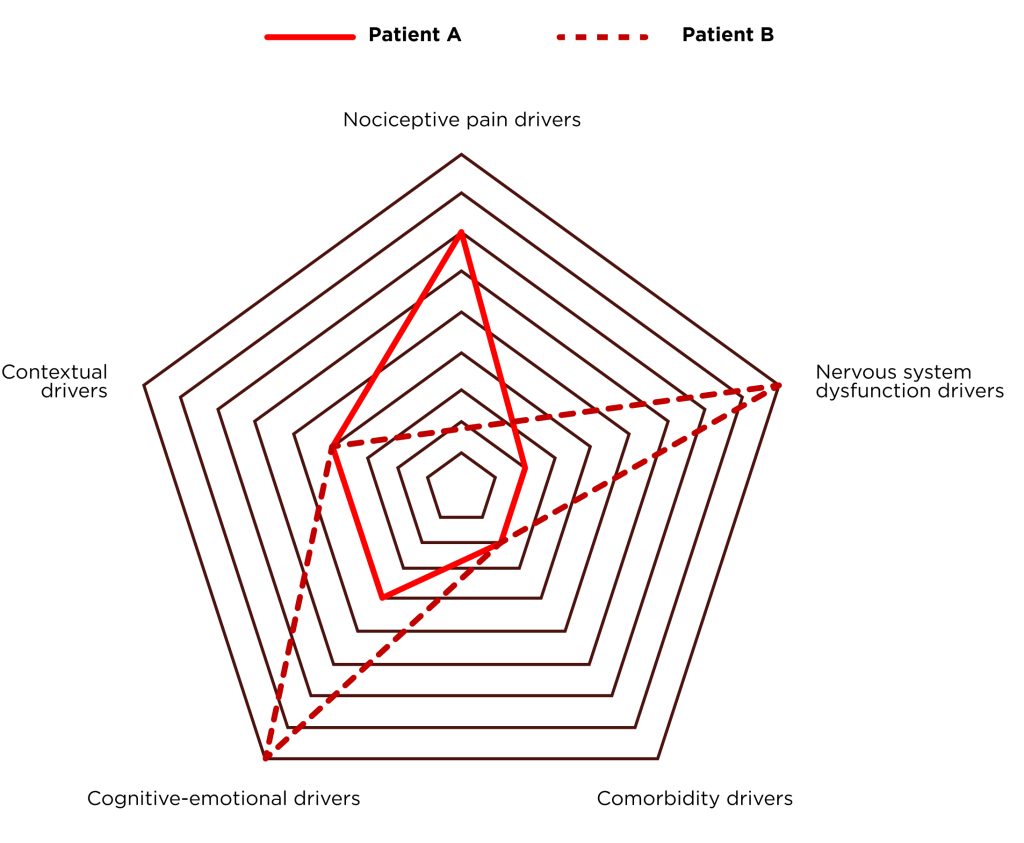

As a both team and individual coach through my years of work me and my team have worked with many different people with various health problems. The majority that come to see us have musculoskeletal pain, but quite often they have other chronic diseases. Every health problem and painful condition is different from one person to another, and for every client we need to have a different approach. Pain is a multifactorial subjective symptom whose origin can be explained only if we consider the complexity of different pain drivers and their interconnections (Figure 1.). The world of fitness and rehabilitation has been dominated by the biomedical model in the past, and this model is focused on anatomical pathology. Due to frequent failures of that model, today we have a relatively new model that is called the Biopsychosocial model. This model, for the explanation of pain, takes into account psychological factors (such as fear and beliefs), social factors (such as job satisfaction), and not only biological factors (such as pathoanatomic) (Liebenson, 2019).

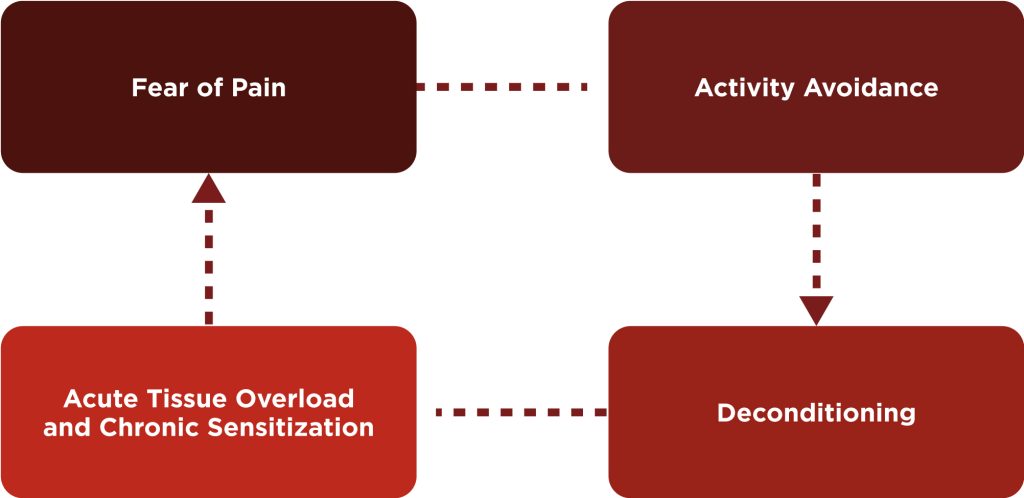

80% of people are dealing with some kind of painful condition. Most often it is lower back pain. It is not hard to identify a common pattern with these individuals. When a person is in pain first thing, he or she often does is activity avoidance which leads to deconditioning of the tissue. When a person is trying to return to normal activity, they experience an acute overload of tissue and often pain which leads to fear of pain and again activity avoidance. This vicious circle is often happening to the general population and the majority of our clients have been, at least once, a part of this circle. The task and the goal is to get the person with pain out of this circle and to give them adequate support for achieving their pain-free goals.

Our approach

Exercise is one of the most effective treatments for treating and preventing painful conditions and chronic diseases. Exercise therapy is equally effective as a medical treatment and in some cases is more effective than medical treatment (Liebenson, 2019). You are probably thinking „Oh, here we go again with this boring exercise is medicine thing”, but when I started writing this blog, I stumbled upon a study written by Pedersen and Saltin (2015). The data from this study was overwhelming. Even I didn’t expect that exercise would have a positive impact on this many health conditions. Kevin Carr from Mike Boyle Strength & Conditioning (one of my biggest influences to become a fitness and strength and conditioning coach) in one of his MBSC Winter seminar lectures said that we as personal trainers are the „First line of healthcare”. If we think about it for a second, what crosses my mind is that if hypothetically one person goes to see a doctor every two months (at my age that is a lot), the doctor sees his patient 6 times per year. My clients see me on average 3 times per week and if we extrapolate that information over the year, my clients see me 24 times more than they see their doctor. It is simple math. On the other hand, if we take a closer look at meta-analyses that quantify the best predictors of all-cause mortality, we can conclude that one of the best predictors are cardiorespiratory fitness or VO2max (Kodoma et al., 2009) and muscular strength (Garcia – Hermoso et al., 2018). We are a big part of the healthcare system and more emphasize should be put on that fact.

As I said before, the Biopsychosocial model is relatively new in fitness and rehabilitation, and we will try to put it into practice. The only way to do that is to have a client-centered approach. This approach addresses the client’s symptoms, dysfunctions (impairments, abilities, and participations), and psychosocial factors (Example 1.).

Example 1: Client X

- Symptom: lower back pain

- Previous injuries: shoulder injury

- Dysfunctions:

a) Impairments: limited hip extension, hip IR, shoulder flexion, plantar flexion and hip extension weakness, high resting heart rate

b) Functional abilities: walking and sitting tolerance

c) Participation: work activity - Psychosocial factors: fear of picking up objects from the floor, anxiety

The biggest problem is the heterogeneous group. On one hand, we have a client who does not have a training background, or they have pain. On the other, we have an advanced group of participants with high levels of cardio-respiratory fitness and muscular strength. Over the past years, we are working on an adaptation training system that can lead people to the desired goals. The starting point of this system and biggest influence was Michael Boyle and his Certified Functional Strength Coach. His progression–regression model has enabled this approach to succeed in group settings.

Based on this approach Client X from Example 1. at first, would not deadlift with external load, he would do hip hinges for proper deadlift technique. For hip dominant strength exercise, he would do glute bridges and then progress to single-leg glute bridges. The famous Dan John quote from his book (2009) „If it is important, do it every day” so Client X would do shoulder and hip mobility exercise every single training session. From his high resting heart rate measurement and training history, we can assume that he has a low aerobic capacity, so he would do some kind of low-intensity aerobic exercise that doesn’t worsen his pain symptoms. Today we know that walking and advice on how to stay active are equally effective as other treatments for nonspecific low back pain (Artus, 2010). The last but equally important thing is pain education of the patient/client to reduce anxiety and fear of activity.

The goal

- Reduction or elimination of pain symptoms

- Reducing the risk of injuries in training or everyday activity

- Progressive improvements of physical abilities related to human health and longevity (VO2max, strength, flexibility)

- Educating clients on pain and the importance of exercise in the prevention of painful conditions and other chronic diseases

Take home message

- To the general population:

Just stay active and exercise on a weekly basis. You don’t need to like it, it needs to be meaningful. I don’t like to run or ride a bike, but I do it anyway because I know it would benefit me in the long run - To fitness an S&C coaches:

Think of yourself not only as a coach but as a healthcare practitioner. Provide movement health to your clients and you can change their lives. In my short career, I’ve had the privilege to work with more than 200 people, that’s 200 opportunities to change somebody’s life. Don’t waste that!

References

- Chantler C. ‘The second greatest benefit to mankind’?. Clin Med (Lond). 2002

- Crimmins EM. Lifespan and Healthspan: Past, Present, and Promise. Gerontologist. 2015

- Park B, Park B, Han H, et al. Projection of the Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years in Korea for 2030. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;34(Suppl 1):e92. Published 2018 Dec 3.

- Barbosa Filho VC, de Campos W, Lopes Ada S. Epidemiology of physical inactivity, sedentary behaviors, and unhealthy eating habits among Brazilian adolescents: a systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2014

- Wu A, March L, Zheng X, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Transl Med. 2020

- Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine : A Patient-Centered Approach. Third ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2020.

- Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015

- Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009

- García-Hermoso A, Cavero-Redondo I, Ramírez-Vélez R, et al. Muscular Strength as a Predictor of All-Cause Mortality in an Apparently Healthy Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Data From Approximately 2 Million Men and Women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018

- John D. Never let go: A Philosophy of Lifting, Living and Learning. On Target Publications; 2017.

- Artus M, van der Windt DA, Jordan KP, Hay EM. Low back pain symptoms show a similar pattern of improvement following a wide range of primary care treatments: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010