At the last UEFA licensing course for conditioning coaches, we discussed testing in soccer during a workshop. The focus was on which tests to conduct, when to conduct them, how to interpret the results, and common challenges like the perceived time constraints. While time management is important, we also need to consider the value of the data collected and how to use it effectively. If the data simply gets stored away and not utilized, it may be a waste of time. However, if used properly, testing offers more benefits than drawbacks.

As knowledge in soccer and related fields grows, new ideas and tools, like invisible testing and monitoring player responses over time without traditional testing days, become more relevant. GPS technology can serve as an excellent tool for this purpose, although that’s not the focus here. In this text, I want to suggest how we can incorporate testing into our warm-up or training protocols instead of setting up traditional testing days. I have been using the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) and Cutting Movement Assessment Score (CMAS) with my teams and players for some time, and I recently discovered the Sprint Mechanics Assessment Score (S-MAS), which adds another piece to the puzzle.

The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is a tool used to identify faulty movement patterns that may increase the risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries, particularly during non-contact incidents. It assesses how well an individual lands from a jump, focusing on the mechanics of the lower extremities.

What is LESS?

LESS is a screening tool designed to evaluate landing technique and identify potential risks for lower extremity injuries. It focuses on specific movement patterns, such as knee valgus (inward collapsing of the knee), excessive leg rotation, and decreased knee flexion, which are commonly associated with ACL injuries. By identifying these patterns, coaches and trainers can implement corrective exercises to improve movement quality and reduce injury risk.

Scoring System

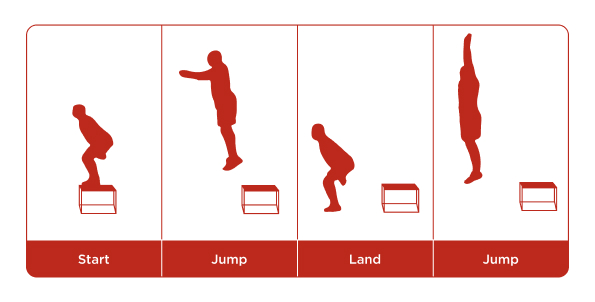

The LESS involves analyzing an individual’s jump-landing technique using a video recording or real-time observation. The client jumps from a 12-inch (30 cm) box and lands just ahead of a marked line, followed by an immediate vertical jump. The fitness professional observes the landing from the front and side to identify any errors in movement.

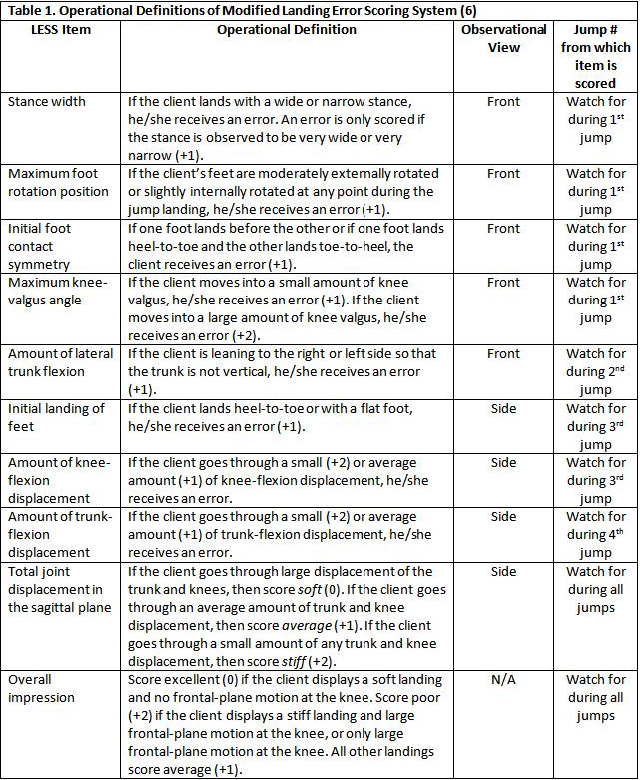

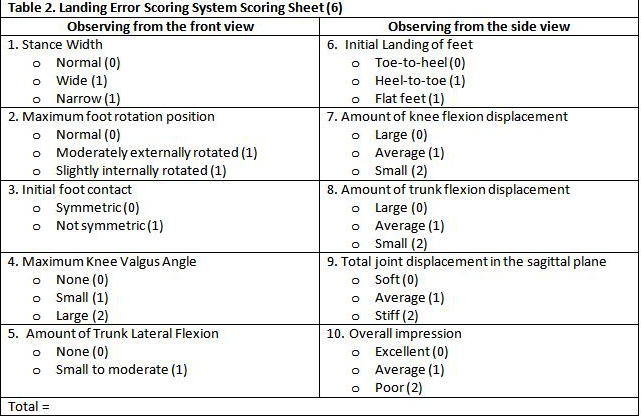

The scoring system is based on 17 different criteria, each focusing on different aspects of landing mechanics, such as foot position, knee alignment, and trunk stability. If a movement error is observed, it is marked on the scoring sheet. The overall LESS score is determined by summing all the identified errors, with a higher score indicating a higher risk of injury due to poor landing mechanics.

Cutting Movement Assessment Score (CMAS) Overview

The Cutting Movement Assessment Score (CMAS) is a qualitative screening tool designed to assess the movement quality of athletes during side-step cutting actions, which are commonly associated with non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. The CMAS evaluates specific postures of the hip, knee, foot, and trunk that are linked to increased knee joint loads and potential ACL loading, thereby testing and identifying athletes who may be at higher risk of injury.

How to Perform the CMAS Testing

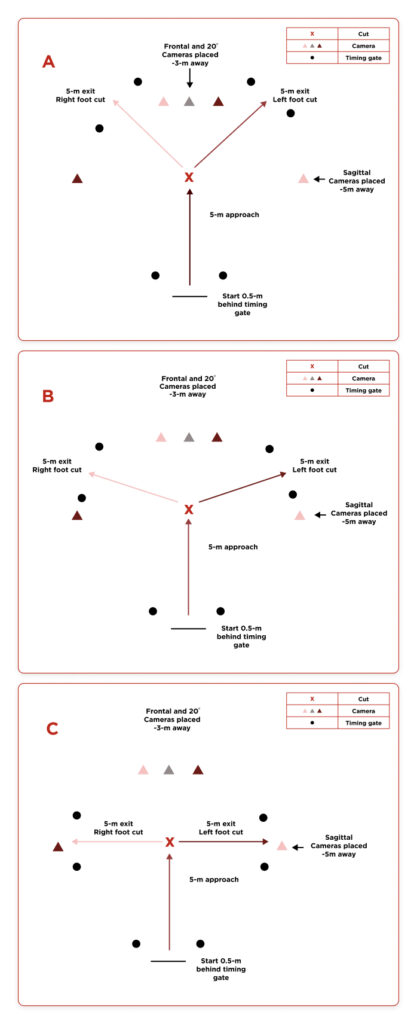

- Setup: Position at least two high-speed cameras (minimum 100 Hz) on tripods at hip height: one in the frontal plane (3 meters away) and one in the sagittal plane (5 meters away) from the cutting zone. If possible, add a third camera at a 20-45° angle relative to the cut to reduce parallax error. Use a cutting task with angles between 30-90°, ensuring athletes perform the task on the same surface they typically compete on, with sport-specific footwear.

- Movement Execution: Athletes perform a side-step cut with a 5-meter entry and exit distance. Record 2-3 trials per limb for each athlete.

- Analysis: Review video footage using software that allows frame-by-frame analysis, such as Kinovea. Evaluate the athlete’s movements using the CMAS criteria, which include nine key items like lateral leg plant distance, initial knee valgus position, and trunk posture during the cut.

- Scoring: Athletes are scored based on their adherence to optimal movement patterns, with higher scores indicating suboptimal technique and a higher risk of injury. Scores of ≥7 are considered high-risk, 4-6 moderate-risk, and ≤3 low-risk.

Sprint Mechanics Assessment Score (S-MAS) Overview

The Sprint Mechanics Assessment Score (S-MAS) is a qualitative screening tool used to assess an athlete’s sprint running mechanics. It evaluates 12 key parameters related to the phases of the sprint gait cycle, such as trailing limb extension, trunk and pelvic rotation, lumbar extension, and foot contact. Each parameter is scored using a binary system: 1 point for the presence of a specific movement pattern considered suboptimal, and 0 points for its absence. The total score ranges from 0 (optimal mechanics) to 12 (suboptimal mechanics), with higher scores indicating poorer technique and potentially higher injury risk.

How to Perform the S-MAS

- Setup: Use a slow-motion camera to record sprint running trials. The camera should capture the sprint from the side view to clearly observe movement patterns.Ideally, the camera should be set up at a distance that allows for clear visibility of the athlete’s movements.

- Movement execution

- The athlete performs a sprint, typically over a distance of 35 meters.

- Record the sprint to capture the key phases of the gait cycle.

- Analysis

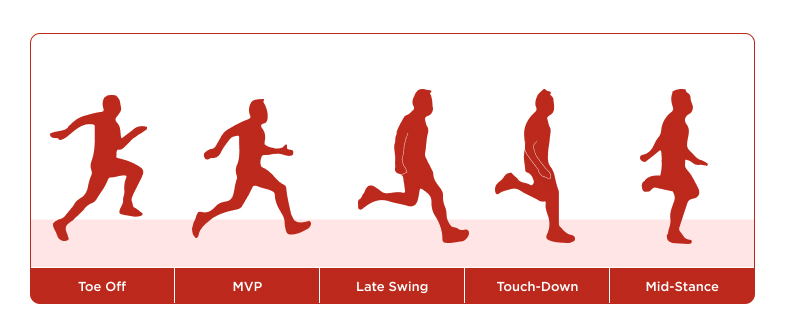

- Review the slow-motion footage and segment it into specific gait phases similar to the ALTIS Kinogram method (e.g., contralateral toe-off, mid-stance).

- Evaluate each of the 12 parameters by observing the athlete’s movement in these phases.

- Scoring

- For each parameter, assign a score of 1 if the movement pattern is present and 0 if it is absent.

- Sum the scores across all 12 parameters to obtain the athlete’s total S-MAS score.

The entire evaluation process can be found here. It is essential to be familiar with the sprint phases proposed by the ALTIS Kinogram method. Since injuries are complex phenomena, often multifactorial, this approach allows practitioners to fill in checkboxes and rule out what may not have caused the issue. These tests can be organized and used daily in your work, and they can also be adapted to the periodization and microcycle in which you are currently working.

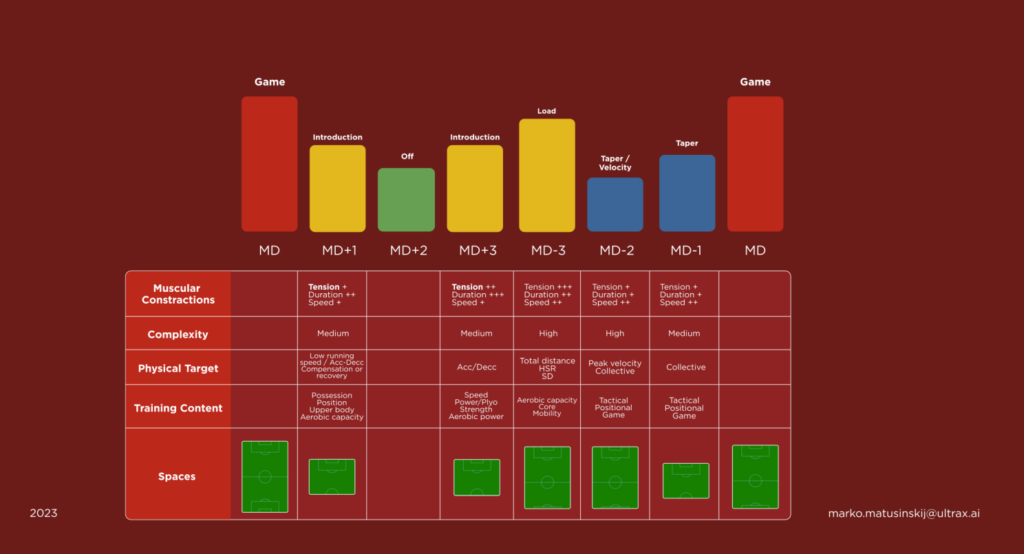

For example, if you have a match on Saturday and the next one is also on Saturday, you might organize a recovery and compensatory training day for players who played less than 60 minutes on MD+1. However, this isn’t always the case, as a player who has already had sufficient chronic and acute load and whose match data was adequate in those 30 minutes might be excluded from compensation. Nevertheless, that’s a different topic. This day could be an excellent opportunity to test players who didn’t play in the specified testing events.

The first segment can be organized through a circuit activation format, where you include core exercises, isometric activations, mobility drills, with one station dedicated to the LESS. After moving to the field, one station can serve as a priming exercise before the first soccer drill, where CMAS can be performed, followed by the S-MAS. The S-MAS can also be used after some circular passing drills, ideally before transitions or games in larger spaces, which will also prepare players for the subsequent session. This way, you ensure that all players are activated and ready for the soccer content while gathering valuable information about them.

On MD+2, the team can be given a rest day, as there’s sufficient time for training before the next match. On MD-4, the team gathers again, and on this first day, LESS and CMAS tests can be performed since they are less demanding on the hamstrings and do not require too much effort from the players. As noted in the latest work by author Carmona (2024) and colleagues, the hamstrings may not be ready for high-intensity activities, and it wouldn’t hurt to gradually “start the engines” at the beginning of the week, as the author Raymond Verheijen likes to say. I personally like this expression and follow it as an unwritten rule.

By MD-3 or three days before the match, players are already integrated into the week, and the coach wants to emphasize tactical ideas, using small-sided games, making it an ideal day to implement the S-MAS testing with your teams. Besides aiding in acute planning, this information can be used to connect the load we applied during the week and how that profile changes. It would also be beneficial to see differences in S-MAS testing results between groups that have had previous hamstring or quadriceps injuries, how these injuries affect results, and if there are differences between players who were injured and those who weren’t, as well as between players before and after an injury.