In the world of sports science, understanding the physical capabilities and limitations of athletes is essential for optimizing performance and preventing injuries. Following our previous exploration into Nordic hamstring strength among Croatian youth football players (check out the previous blog here), this blog delves into the assessment of abductor and adductor strength using VALD technology.

Assessing Muscle Strength

Injuries in football are a common occurrence, often linked to imbalances in muscle strength and flexibility. The adductors and abductors, which play pivotal roles in stabilizing the pelvis and facilitating movements like kicking and changing directions, are particularly susceptible to strains and tears. Additionally, plantar flexion, the movement that involves the foot and ankle, is critical for explosive movements such as sprinting and jumping. Identifying weaknesses and imbalances in these areas is crucial for developing targeted training and rehabilitation programs.

In this article I will not go into analysis of the asymmetries and differences between the results, I just want to show the data that we randomly collected from different Croatian clubs. We would like to emphasize the importance of continuous work to at least reduce the time spent off the field due to unnecessary injuries and to provide some strategies what coaches can do with their players. You would be surprised what we can accomplish with just a proper warm up strategy or basic monitoring tools.

Methods

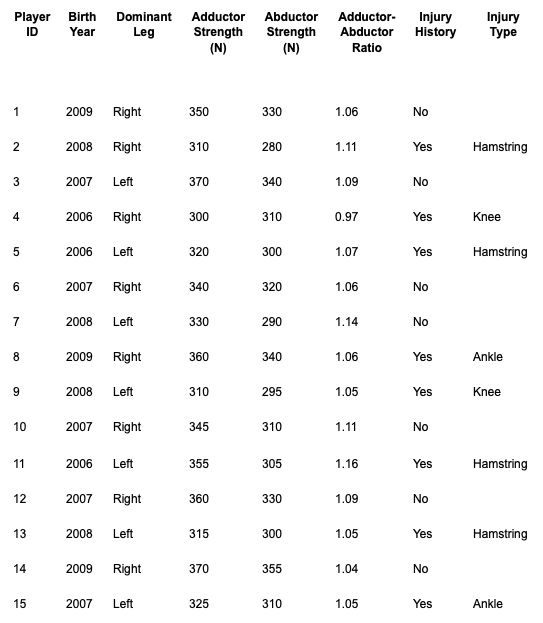

The “study” involved 15 youth football players born between 2006 and 2009. Each player’s dominant leg, adductor and abductor strength, adductor-abductor ratio and injury history were recorded. The results are summarized in the table below:

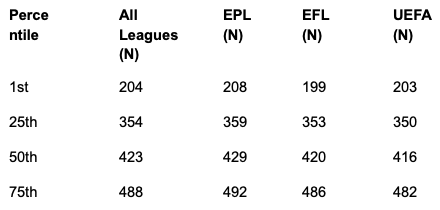

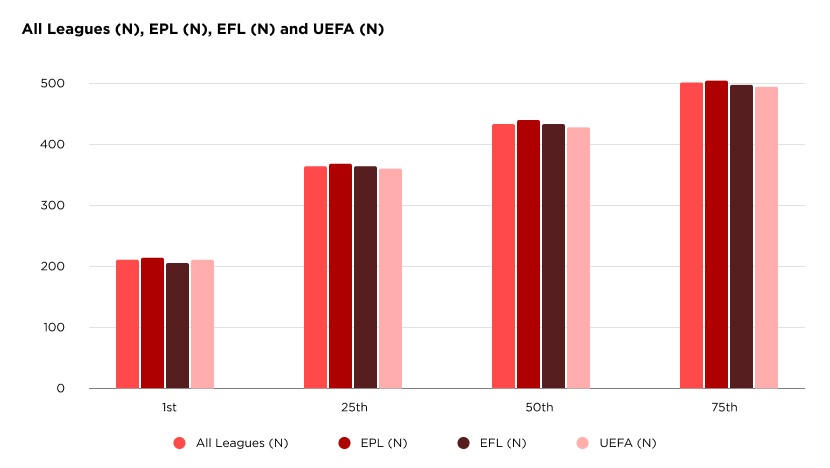

Adductor Strength Comparison of Croatian players to normative values from VALD Hub

1st percentile: Croatian young players have adductor strengths well above the 1st percentile for both professional leagues and age groups, indicating they are not in the lowest performing group.

25th percentile: Croatian players mostly fall around or slightly above the 25th percentile of professional leagues but are within the 25th percentile for their respective age groups (15-16 and 17-18 years old).

50th percentile: Croatian players are generally below the median for professional leagues, aligning more closely with the median for younger age groups (13-16 years old).

75th percentile: None of the Croatian players reach the 75th percentile for either professional leagues or older age groups (17-20 years old).

Adductor-Abductor Ratio Comparison

1st percentile: Croatian players’ ratios are above the 1st percentile for all age groups, indicating they avoid the lowest ratio benchmarks.

25th percentile: Croatian players’ ratios are mostly above the 25th percentile for all age groups, showing they have better ratios than the bottom quarter of their peers.

50th percentile: Most Croatian players have ratios close to or above the median for age groups up to 16 years old, but may fall slightly below for older age groups (17-20 years old).

75th percentile: A few Croatian players achieve or exceed the 75th percentile ratio for age groups up to 16 years old, but less so for older age groups.

Conclusions and Discussion

Performance Relative to Professional Leagues

Croatian young players’ adductor strengths are below the median for professional leagues, indicating they have room for improvement to reach the average professional player’s level.

Age Group Comparisons

Croatian players compare more favorably within their age groups, especially the younger ones (13-16 years old). They generally perform around or slightly above the median, suggesting they are developing well for their age but need to continue improving to compete with older age groups and professional standards.

Injury Considerations

Players with injury histories, particularly those affecting the hamstring or knee, generally have lower adductor strengths.

25th Percentile Comparison

- Ratios: Croatian players’ ratios are mostly above the 25th percentile for all age groups, showing they have better ratios than the bottom quarter of their peers.

- Adductor Strength: Croatian players mostly fall around or slightly above the 25th percentile of professional leagues but are within the 25th percentile for their respective age groups (15-16 and 17-18 years old).

50th Percentile (Median) Comparison

- Ratios: Most Croatian players have ratios close to or above the median for age groups up to 16 years old but may fall slightly below for older age groups (17-20 years old).

- Adductor Strength: Croatian players are generally below the median for professional leagues, aligning more closely with the median for younger age groups (13-16 years old).

75th Percentile Comparison

- Ratios: A few Croatian players achieve or exceed the 75th percentile ratio for age groups up to 16 years old, but less so for older age groups.

- Adductor Strength: None of the Croatian players reach the 75th percentile for either professional leagues or older age groups (17-20 years old).

Strength Deficits in Croatian Youth Football Players

None of the Croatian players are close to the 75th percentile, neither compared to professional players nor to their peers. This lack of strength in the adductor region is just one isolated data point, but it follows a pattern seen in previous tests from the last blog we shared.

From experience, it is also possible to conclude that players are not adequately adapted to senior football, which demands higher loads. Considering that football schools often conduct only 5-7 hours of training with one match per week without delving into load distribution, even this number seems low. When we add insufficient time dedicated to training with external loads or poor organization of the already limited time, the chances of missing something are much higher.

Training vs Match Loads: The Mismatch

What often happens in our training processes is that training loads do not match the loads that occur during matches. With the increasing availability of GPS technology, we can see the distance players have covered at a certain speed or how many activities they have accumulated in a particular zone (number of explosive efforts, number of accelerations, etc.).

However, we must not forget the context, i.e., how these numbers were accumulated, not just think about the total number. Perhaps we had a period of 30 seconds of high-intensity work, where a player had to perform a defensive transition and press an opponent after a wrong pass, then suddenly change direction by 180 degrees and head in the opposite direction to join his team’s attack, where he started moving at a speed of 25 kilometers per hour, reaching a heart rate of 170 beats per minute. During this action, he had one tackle, one pass, and a zigzag sprint, figuratively covering 250 meters in a minute.

In the study “Worst Case Scenarios in Soccer Training and Competition: Analysis of Playing Position, Congested Periods, and Substitutes” by Lukasz Bortnik et al. (2023), the authors analyzed worst-case scenarios in professional soccer by monitoring 31 players from an Israel Premier League team over 37 matches and 14 training sessions. They found significant differences between matches and training in total distance, high-speed running, sprint distance, and maximum deceleration across all positions. Fullbacks differed in maximum acceleration, while center backs and central midfielders differed in maximum deceleration. Nonstarters lacked high-intensity exposure, especially during congested periods.

The study concluded that training does not replicate the high-intensity actions seen in matches, highlighting the need for tailored training to address this gap.

And that is something that can often be seen on the fields. Just recently, I had a meeting where we discussed how much can be achieved with just good organization and establishing basic habits in working with athletes. I would say a lot, if you know what to look for. I would say that it is possible to establish a high-performance environment with minimal conditions. One of the leading problems often cited is the lack of time and resources. In my opinion, the most important resource is quality people, coaches.

What I don’t like too much in our systems today is that the individual is generally a jack of all trades and doesn’t have the support because the necessary resources are often missing. If you ask me, it’s people who make the system, and people need to be guided and rewarded for effective work. What can help in such cases is the application of technology, which is easily accessible today, to assist coaches in these problems by providing a simpler way to collect, analyze, present, and communicate everything related to their team or individual players.

What gave me a WOW effect was the chatbot we created for our needs (we’ve been shaping it according to some of our ideas for the last month). What our chatbot can do is answer basic queries from coaches about program creation, guide them if they have any doubts, or prepare an automated report. What is important in this case is to provide it with context so that the response is as accurate as possible. For now, it looks promising.

Adductor Injury Prevention Protocol

1. Warm-up

- Start with a general warm-up to increase heart rate and blood flow to muscles (e.g. jogging, dynamic stretching).

- Include specific warm-up exercises targeting the adductors (e.g. lateral leg swings, groin stretches, frogs).

2. Strengthening Exercises

- Adductor Squeeze: Use a ball or a pillow between the knees and squeeze for 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

- Side-Lying Hip Adduction: Lie on your side and lift the bottom leg upwards for 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

- Standing Adductor Strengthening: Use resistance bands to add resistance while performing adduction movements for 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

- Copenhagen exercise different levels: One can play with the type of contraction and duration of contraction and the lever of the leg to decrease or increase the load on adductors.

3. Stability and Balance Exercises

- Single-Leg Stance: Stand on one leg for 30 seconds, progressing to closing eyes or standing on an unstable surface (e.g., a balance pad).

- Lateral Lunges: Perform lateral lunges focusing on controlled movement and proper alignment for 3 sets of 10 repetitions on each side.

4. Monitoring and Progression

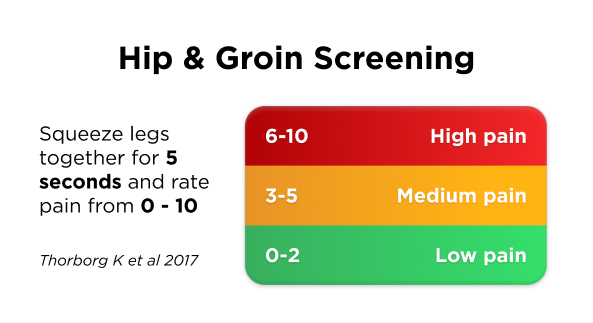

- Regularly assess adductor strength and flexibility, you can perform 5 seconds adductor squeeze test every day or check internal and external hip rotation.

- Gradually increase the intensity and volume of exercises as strength and endurance improve.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the team at GNK Dinamo Zagreb for their support and collaboration in conducting these assessments. Special thanks to Sebastjan Potokar and Luciano Tomaghelli from VALD Performance for their invaluable expertise and assistance.