Einführung

Dieser Text soll dazu dienen, den Ablauf eines Trainingstages im Fußball zu veranschaulichen. In letzter Zeit ist es recht populär geworden, wissenschaftliche Begriffe zu verwenden und jede Arbeit mit wissenschaftlichen Beweisen zu untermauern, aber in der Welt des Fußballs wurden manche Dinge noch nicht getestet oder sind einfach nicht so einfach zu bestätigen. Wenn Sie im Fußball arbeiten und mit der Literatur vertraut sind, haben Sie vielleicht gesehen, dass eine Fußballmannschaft aus mehreren Gruppen von Spielern besteht, die am Wettbewerb teilnehmen. Zu diesen Gruppen gehören Stammspieler, Ersatzspieler, Mitglieder der Reisemannschaft, die nicht am Spiel teilgenommen haben, nicht mitreisende Spieler, Spieler im Rehabilitationsprozess, Spieler in Nationalmannschaften und schließlich eine spezielle Gruppe – diejenigen, die in Ihr Vorbereitungs- oder Wettkampfsystem einsteigen, ohne am Trainingsprozess der Mannschaft teilgenommen zu haben.

Jede dieser Spielergruppen erfordert einen anderen Ansatz, wenn es um die Programmierung von Trainingsbelastungen und die Gestaltung eines Trainingstages geht. Zusätzlich zu diesen Spielergruppen gibt es noch weitere interessante chaotische Szenarien, die Ihre Entscheidungen bei der Gestaltung eines Trainingstages im Fußball beeinflussen werden. In diesem Text werde ich versuchen, diese Szenarien zu erwähnen. Bevor wir jedes davon im Detail erklären, listen wir sie zunächst auf:

- Letztes Spieldatum

- Im Spiel gespielte Minuten

- Nächster Spieltermin

- Senioren- oder Jugendfußball

- Länge der Woche

- Spielhäufigkeit (ein oder zwei pro Woche)

- Teamstatus für diese Woche oder diesen Tag – Überwachung

- Wöchentliche und Trainingstagesziele

- Anzahl verfügbarer Spieler

- Diskussion mit dem Trainer

Letzter Spieltermin und nächster Spieltermin

Es ist schwer zu sagen, welche der oben aufgeführten Faktoren die wichtigsten sind, da jeder einzelne den Verlauf eines Trainingstages bestimmen kann. Der Zeitpunkt des letzten und des nächsten Spiels hat jedoch erhebliches Gewicht.

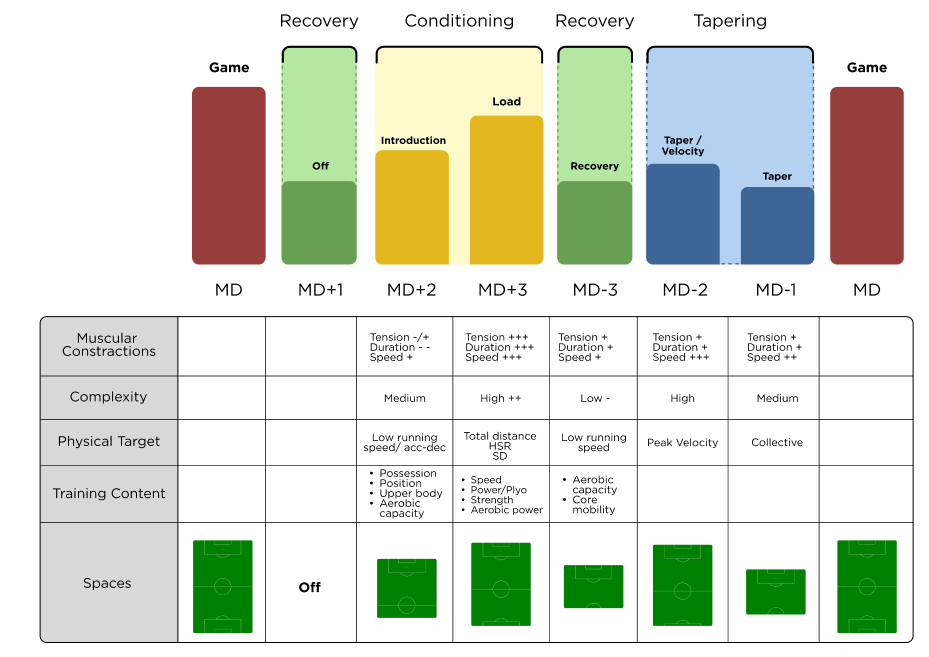

In der Fußballterminologie verwenden wir Begriffe wie MD- (Spieltag minus) und MD+ (Spieltag plus), um anzugeben, wo wir uns auf der Zeitleiste befinden. MD- steht für die Anzahl der verbleibenden Tage bis zum nächsten Spiel, während MD+ angibt, wie viele Tage seit dem letzten Spiel vergangen sind.

Typischerweise werden drei Begriffe genannt (je nach Wochenlänge): MD+1, MD+2 und MD+3. In der Praxis wird man am häufigsten auf die ersten beiden Begriffe stoßen, die zwei Tage mit Erholungscharakter symbolisieren. An diese Tage werden bestimmte Merkmale geknüpft, die sie definieren.

Im Fußball gibt es unterschiedliche Spieltage – Spiele können freitags, samstags, sonntags und mittwochs stattfinden. Da jeder Spieltag und die Tage um ihn herum unterschiedliche Charakteristika haben, symbolisiert MD+1 bei der Notation MD-/+ immer den Tag nach dem Spiel, der seine eigenen Besonderheiten hat. So ist für mich als Konditionstrainer und für das Trainerteam klar, welche Inhalte an diesem Tag umgesetzt werden können.

Der Prozess der Zusammenstellung eines Trainingstages nach einem Spiel beginnt unmittelbar nach dem Ende des Spiels. Ein wichtiger Faktor bei der Erstellung des Plans für den nächsten Tag ist definitiv der Ort des Spiels. Wenn wir ein Heimspiel hatten, schlage ich normalerweise vor, das Training für 11:00 Uhr am nächsten Tag anzusetzen. Ich glaube, dass die Spieler mit diesem Zeitplan genügend Zeit zum Ausruhen, Schlafen und Frühstücken haben, bevor sie zur Nachbeurteilung und Trainingseinheit, die sich normalerweise auf die Erholung konzentriert, in die Anlage kommen.

Bei einem Auswärtsspiel mit kürzerer Anreise können wir uns dennoch für einen ähnlichen Trainingsplan wie im ersten Szenario entscheiden. Bei Spielen mit langer Anreise kann jedoch manchmal darauf bestanden werden, dass die Mannschaft am Spielort übernachtet. Dies gibt den Spielern genügend Zeit, um gut zu schlafen und sich auszuruhen, was für eine ausreichende Erholung entscheidend sein kann. In solchen Fällen wird die Trainingseinheit normalerweise am zweiten Tag nach dem Spiel angesetzt, als MD+2 gekennzeichnet und hat typischerweise einen erholungsorientierten Charakter.

Spieltag +1

Der Tag nach dem Spiel wird dazu genutzt, so viele Informationen wie möglich über alle Spieler zu sammeln, die am Spiel teilgenommen haben, unabhängig von ihrer Zeit auf dem Spielfeld (auf Kompensationstraining und reduzierte Spielzeit werde ich später eingehen). Spieler, die mehr als 60 Minuten gespielt haben, werden mit ziemlicher Sicherheit müde sein – um ihren Zustand zu verfolgen, verlassen wir uns auf eine Kombination aus Wellness- und TQR-Fragebögen (Total Quality Recovery). Die Dauer und Qualität des Schlafs werden ebenfalls vom Spiel beeinflusst, daher muss dieser Aspekt bei der Untersuchung der Fragebogenantworten ebenfalls berücksichtigt werden.

Während des Trainings interessiere ich mich für schmerzende oder entzündete Stellen, damit ich mich sofort darum kümmern oder den Spieler anweisen kann, sich an einen Physiotherapeuten oder Arzt zu wenden. Es ist wichtig, sich nicht von der Spieldauer täuschen zu lassen – es gab Fälle, in denen Spieler, die 45 Minuten auf dem Feld standen, eine höhere Intensität und Aktionsdichte zeigten als diejenigen, die 60 Minuten spielten. Das soll uns daran erinnern, dass wir den Spielkontext nie vergessen sollten.

Trainer machen oft Kommentare wie: „Lasst sie am regulären Training teilnehmen, es war nur ein 45-minütiges Spiel, was könnte da schon schiefgehen?“ Das mag zwar in manchen Fällen zutreffen, aber durch den Zugriff auf Mikrotechnologie oder GPS-Systeme können wir die wahre Belastungsstufe während dieser 45 Minuten erkennen. In einem solchen Spiel lagen wir zurück und mussten aufholen, also setzte der Trainer offensivere Spieler ein, die das Spiel die ganze Zeit über verfolgen mussten, um einen Punkt zu retten oder alle drei Punkte zu sichern.

Meine Empfehlung für MD+1 war nicht, dass sie das Training ausfallen lassen und sich ausschließlich auf die Erholung konzentrieren sollten, sondern dass sie Aktivitäten durchführen sollten, die sie während des Spiels nicht ausreichend gemacht haben – in diesem Fall Volumen. Um die während des Spiels erfassten Messungen grob einzuteilen, würde ich drei Kategorien nennen:

- Beschleunigungen, Verzögerungen und Richtungswechsel

- Hochintensives Laufen mit Geschwindigkeiten über 19,8 km/h

- Zurückgelegte Gesamtstrecke

Wir können auch Kategorien für Schüsse, Luftduelle und Bodenduelle hinzufügen. Normalerweise würde ich Spieler, die mehr als 60 Minuten gespielt haben, am MD+1 ins Regenerationstraining schicken. Andere Spieler mit weniger Spielzeit nehmen an Kompensations- oder Ausgleichstrainings teil, um die Spielbelastung zu simulieren und mit der Startelf synchron zu bleiben.

Ersatzspieler konzentrieren sich auf Aktivitäten, die die verpassten Aktivitäten nachholen. Wenn Sie keinen Zugriff auf GPS-Daten haben, kann die Videoanalyse des Spiels Einblicke in die Aktionen des Spielers während des Spiels geben. Was sicherlich nachgeholt werden muss, ist das Spielvolumen und einige hochintensive Aktivitäten.

Von der Umkleidekabine aufs Spielfeld

Sobald ich im Verein ankomme, besuche ich als Erstes die Physiotherapie- und Behandlungsräume. In einem kurzen Meeting von 10 bis 20 Minuten kann ich alle Informationen sammeln, die ich über den Zustand des Teams brauche, um den Trainingstag zu planen. Nach diesem Meeting treffe ich mich mit dem Cheftrainer und dem Trainerstab zu einem ausführlichen Gespräch, in dem wir die Aktivitäten jedes Spielers für MD+1 planen. Sobald wir festgelegt haben, welche Spieler an welchem Aspekt des Trainings beteiligt sein werden, fahre ich mit der Ausarbeitung der Trainingsinhalte fort.

Typischerweise werden die Trainingsinhalte in zwei Gruppen aufgeteilt: Eine Gruppe konzentriert sich auf das Erholungstraining, während die andere Gruppe am Kompensationstraining teilnimmt.

Nach dieser Phase gehe ich auf das Feld oder in die Halle, um alles Notwendige für die Trainingseinheit vorzubereiten. Zusätzlich führe ich individuelle Vorbereitungen durch oder führe zusätzliche Tests für Spieler durch, die der Kompensationstrainingsgruppe zugewiesen sind. Diese Tests können Bewertungen wie den 5-Sekunden-Adduktoren-Squeeze-Test, Weitsprungbewertungen oder Gegenbewegungssprünge umfassen.

Wiederherstellungsgruppe

Wir beginnen unsere Trainingseinheiten mit myofaszialen Entspannungsübungen, wobei wir uns auf bestimmte Körperregionen wie die Vorder- und Rückseite der Oberschenkel und die Adduktoren konzentrieren. Nachdem ich diese kritischen Bereiche behandelt habe, nehme ich mir ein paar zusätzliche Minuten Zeit, um an den Regionen zu arbeiten, die für sie wichtig sind.

Myofasziale Entspannung ist eine Technik, bei der Druck auf bestimmte Punkte ausgeübt wird, wie in der Arbeit von Hopper und Deacon (2015) untersucht [1], um angesammelte Muskelspannungen zu lösen. Laut Untersuchungen von Cheatham und Kolber (2015) [2] können diese Techniken die Muskelflexibilität deutlich verbessern. Eine erhöhte Flexibilität ermöglicht es Sportlern, einen größeren Bewegungsbereich zu erreichen und so das Verletzungsrisiko zu verringern. Dies wird durch die Ergebnisse von Weerapong, Hume und Kolt (2005) unterstützt [3], was auch darauf hinweist, dass myofasziale Massage helfen kann, Entzündungen in Muskeln und Gewebe zu reduzieren.

Darüber hinaus kann eine verbesserte Blut- und Lymphzirkulation durch die myofasziale Entspannung zu einem effizienteren Abtransport von Abfallprodukten aus den Muskeln beitragen, was zu einer schnelleren Erholung und weniger Entzündungen nach dem Spiel führt.

Auch der psychologische Aspekt darf nicht unterschätzt werden. Meiner Erfahrung nach haben Spieler zunächst Vorbehalte gegenüber dieser Behandlungsform, ändern aber oft ihre Einstellung, wenn sie die Vorteile selbst erleben.

Bei meiner Arbeit mit der Frauenfußballmannschaft WFC Dinamo begann ich, myofasziale Entspannungstechniken und individuelle Vorbereitungsroutinen vor unseren Trainingseinheiten einzubauen. Anfangs gab es etwas Widerstand, und es dauerte einige Zeit, die Spielerinnen über die Bedeutung dieser Techniken aufzuklären und sie von den Vorteilen zu überzeugen. Heute, nach mehreren Monaten Arbeit, ist es für sie zur zweiten Natur geworden; sie widmen selbstständig 15 bis 20 Minuten im Fitnessstudio ihren individuellen Vorbereitungen, bevor wir mit unserem Mannschaftstraining beginnen.

Im Anschluss an die Entspannungsphase bauen wir statische Dehn- und Beweglichkeitsübungen in unseren Tagesablauf ein. Statische Dehnübungen zielen auf vier wichtige Muskelregionen ab, und diese Übungen sind normalerweise in jeder Erholungstrainingseinheit enthalten:

- Dehnung des Oberschenkelmuskelbands

- Froschstrecke

- Dehnung der Hüftbeuger

- Wadendehnung

Die Entspannungs- und Dehnübungen dauern in der Regel 30 bis 60 Sekunden pro Muskelgruppe. Anschließend geht es weiter mit Mobilitätsübungen, Ziel ist es, die Beweglichkeit des gesamten Körpers zu verbessern. Obwohl wir aufgrund ihrer Wichtigkeit der Hüftbeweglichkeit Priorität einräumen, versuchen wir, alle Körperregionen abzudecken.

Normalerweise gibt es 3 bis 6 Übungen für jedes Gelenksystem. Jede Übung umfasst entweder 10 bis 20 Wiederholungen oder eine Haltezeit von 30 bis 60 Sekunden. Das Hauptziel in dieser Phase ist es, den Bewegungsradius unserer Spieler deutlich zu erhöhen. Denn nach dem Spiel lässt die Flexibilität häufig nach, und wenn dies nicht behoben wird, kann dies zu potenziellen Problemen innerhalb des Teams führen. Deshalb ist unser Fokus auf Mobilität so wichtig – er hilft, solche Probleme zu vermeiden und stellt sicher, dass unsere Spieler ihr Leistungsniveau halten.

Ohne auf die einzelnen Komponenten der Erholungsgruppe näher einzugehen, werde ich die anderen kurz erwähnen. Nach Entspannungs-, Dehnungs- und Beweglichkeitsübungen führen wir Atemübungen, Rumpfaktivierungsroutinen und Kraft- oder Hypertrophieübungen für den Oberkörper durch. Die Wahl der Trainingsmethode ist insbesondere bei unseren Hauptübungen entscheidend. Zum Abschluss unserer Sitzungen schließen wir oft eine 20-minütige Radtour oder einen leichten Lauf um das Feld ab. Trainer fügen oft gerne etwas Fußballtennis hinzu, um für einen kurzen und unterhaltsamen Aktivitätsschub zu sorgen.

Ein Aspekt, der in letzter Zeit mein Interesse geweckt hat, ist aerobes Training und Kapillarisierung, also habe ich begonnen, es wann immer möglich zu verwenden. Dies ist normalerweise am MD+1, aber wir versuchen, es häufiger einzubauen. Diese Idee wurde durch ein Gespräch inspiriert, das ich mit Marc Cleary zum Thema Erholungsmarker hatte (das Sie hier anhören können: Marker der Genesung mit Marc Cleary. Marc erwähnte, dass in der NBA am Tag nach einem Spiel oft leichte Wurfübungen durchgeführt werden und dass sogar eine 20-minütige Einheit, die leichtes Schwitzen hervorruft, eine positive antioxidative Wirkung haben kann. Ein weiteres interessantes Beispiel, das ich erlebte, war das Hockeytraining, das mich wirklich überraschte. Fast täglich wurde ein Kapillarisierungstraining für 20 bis 45 Minuten eingebaut. Anfangs wurde es manchmal in drei Abschnitte zu Beginn, in der Mitte und am Ende der Trainingseinheit unterteilt. Für diese Art von Training gefiel mir Joel Jamesons Begriff „Rebound-Training“.

Verweise

- Hopper, D. und Deacon, S., 2015. Das Miofascial-Release-Technikkonzept: Funktionelle Anatomie. Georg Thieme Verlag.

- Cheatham, SW und Kolber, MJ, 2015. Die Auswirkungen der Selbstmyofaszialen Entspannung mithilfe einer Schaumstoffrolle oder eines Rollenmassagegeräts auf den Bewegungsbereich der Gelenke, die Muskelregeneration und die Leistung: eine systematische Überprüfung. Sportphysiotherapie, 16(1), S. 87-93.

- Weerapong, P., Hume, PA, und Kolt, GS, 2005. Die Mechanismen der Massage und ihre Auswirkungen auf Leistung, Muskelregeneration und Verletzungsprävention. Zeitschrift für Sportwissenschaft und Medizin, 4(1), S. 1-13.